By Paco de Otrome Jico

We first visited Tlaxiaco on the day after American Thanksgiving in 2015. My journal of that adventure reads:

Day twenty-six on the road. Another beautiful morning. Jorge our driver appeared at nine am and we headed toward the Triqui indiginas. These are the people dressed in long red gowns. The market in their region is at Santa María Asunción Tlaxiaco, over a hundred kilometers west of Oaxaca de Juárez. The ride carried us through mountains with spectacular geological road cuts illustrating the dynamic fault zone that cuts across Mexico at this latitude.

We stopped at the sixteenth-century church at San Juan Teposcolula. Quite a spectacle both inside and out. Huge, tall, massive. With stops took us 3.5 hours to reach Tlaxiaco.

Saw no indiginas when we rolled into town. Located the market and there found indiginas, but not too many. The main market is tomorrow Saturday. The gowns they wear, truly long huipiles, ranged in price from 2000-3000 pesos, a healthy chunk of cash and we passed. Scored some black pottery quite unusual. Whistles in the form of birds, frogs. Not really a good artesania market, but an authentic indigenous town. The bank there gave 15.90 to the dollar. Then we rolled back to the capital, admiring the mountains.

Only months after our visit to Tlaxiaco, we moved permanently to Oaxaca de Juárez. Although Tlaxiaco remained on our minds, we kept putting other adventures ahead of it. Then the covid pandemic of 2020-2021 closed the Tlaxiaco market for almost two years, keeping us away still longer. Finally, in 2022, the plaza reopened, and we made plans to travel there.

The Little Paris and the Porfiriato

Wise travelers learn the history of a destination before arriving there. This enhances the experience by providing perspective for the traveler. Our research taught us that the prosperous and rich area of Tlaxiaco was coveted by the Aztecs, who called the region “Buena Vista,” so they established a garrison there, which they named Tlachquiauhco, meaning “In the Place of the Ball Game Rain.” When the Spanish invaded and conquered the region in 1521-1522, they subjugated the indiginas, exploiting them while enriching themselves, and renamed the people Mixtecs. The Dominicans subsequently converted the Mixtecs to Catholicism, changing the original culture forever.

In October 1852, the Mexicans, having expelled the Spanish, elevated the community of Tlaxiaco to the status of “town.” Subsequently, because of its victory in the 1814 battle of Cerro Encantado, and events during the Reform Period beginning in 1854, the “town” was further elevated in 1860 to “Heroic to the Villa of Tlaxiaco.” Additional elevation was granted twenty-four years later, when the “villa” became the “Heroic City of Tlaxiaco” in 1884. Final elevation occurred in 1984, when the formal name of La Heroica Ciudad de Tlaxiaco was bestowed upon the “city.” Of most interest, however, we learned that Tlaxiaco is known colloquially as “The Little Paris.”

To best understand the anointment of the town as “The Little Paris,” a brief introduction to Porfirio Díaz is necessary. This native of Oaxaca de Juárez, born to a Creole father and a half-Mixtec mother, was raised in extreme poverty, worked at one time as a bootblack, and used his rise through the military to become a dictator of Mexico that ruled in command for thirty years, one hundred and five days, during the span 1876 to 1911, a period of power not equaled before or since, known as the Porfiriato.

Díaz had all the traits of a soldier trained on the battlefields. He was brusque, rough in his way of dealing with people, but with an adequate vocabulary to assert himself above of his soldiers. He lacked social grace, actually intentionally disrespecting it – he was accustomed to spitting and purposeful flatulence. However, his second wife Carmen, whom he met at a political class party, devoted herself to educating him in Mexican society. She taught him the English language, notions of the French language, the manners of high society, the way of moving and expressing oneself, the proper way of eating, and the appropriate vocabulary for each situation. His social improvement caused his humble name of just Porfirio to become elevated to the authoritative Don Porfirio.

Díaz feared speaking in public, avoiding it unremittingly. On one occasion he relented. After several attempts to orate, he gave up, and he began to cry at the lectern, an act exposing him as a sissy, casting him into the role of laughingstock of the Mexican political class. On another occasion, when defeated and dejected in an election prior to his dictatorship, he cried in public, earning the nickname El Llorón, the crybaby.

The Porfiriato was based on the philosophy of positivism, which preached order and peace. When Díaz came to power, the Mexican government was in debt and had very few cash reserves. Among the main visions of the Díaz mandate was the growth of foreign investment and the development of capitalism in the Mexican economy. To accomplish this, Díaz enthusiastically encouraged investment by foreigners, and since Díaz was no economist, so he sought advisers to find foreigners. Because incentives were made so advantageous to the suppliers of capital, these advisers enjoyed great success. Con dinero baile el perro. With money the dog dances. They were instrumental in forging diplomatic activity that led to a friendly relationship with the United States, making Mexico an attractive investment destination.

With the arrival of capital in Mexico came the need to create a transport infrastructure that would allow the development of industry, thereby providing communication between the various regions of the country. The construction of railways was arguably the most important aspect of the Mexican economy in the Porfiriato. Ironically, trains provided the essential ingredient for the successful Revolution of 1910 and the downfall of the dictator. Díaz is also credited with construction of streets, monuments, and buildings.

When Díaz arrived on the scene, he knew that since the end of the 18th century, continuous political, social and economic instability had prevented the establishment of a favorable climate for science and education in Mexico. The peace that was imposed during the Porfiriato allowed the development of culture and science in Mexico. Under the Díaz command, literature, painting, music, and sculpture flourished. Scientific activities were promoted by the government, since it was considered that a scientific advance in the country could lead to positive changes in the economic structure.

Public education was favored by positivism, and the foundations of that social good were laid during the Porfiriato. It was during the Porfiriato that institutes, libraries, scientific societies and cultural associations were founded. In the same way, popular art sought in the culture of Mexico an element to capture its compositions and express itself, and thus samples of Mexican art were exhibited throughout the world. Positivism managed to cause a revival of the study of national history in Mexico, as an element that entrenched Díaz in power and contributed to national unity. Literature was the cultural field that perhaps made the most progress during the Porfiriato.

But all was not rosy during the Porfiriato. Scandal and labor strife appeared. In November 1901, police raided what would come to be known as the “Forty-One Ball, a party for gay men, at which half of them were cross-dressing. A rumor spread that in reality there had been 42 detainees, number forty-two being the presidential son-in-law. The term “forty-one” means a male homosexual in today’s Mexico.

Workers became discontented. Conditions were made so advantageous to the suppliers of capital that Mexican industries and workers alike suffered. Moreover, Mexico’s new wealth was not distributed throughout the country. Most of the profits went abroad or stayed in the hands of a very few wealthy Mexicans. By the turn of the century, the economy had declined and national revenues were shrinking, which necessitated borrowing. With wages decreasing, strikes were frequent. Agricultural workers were faced with extreme poverty and debt.

At that time , Díaz created the rural corps, a police division disguised as civilians and whose main function was to detect opponents of the regime and execute them by firing squad. A tactic of the rurales was the use of the flight law, which consisted of letting the prisoner escape, and then executing him under the pretext of preventing his escape. The rural police officers were better paid and trained than the army, and they were the tool on which Díaz relied to pacify the country.

Inspired by the labor movement that had emerged in the United States, Mexican workers wanted to be able to recover their decent working conditions, and they took to the streets in unparalleled demonstrations. The Strike of Cananea in June 1906, the Strike of Río Blanco in 1907, and the Rebellion of Acacuyan in 1906 were the main labor difficulties of the Porfirista era. The Mexican press sponsored a smear campaign against Díaz as a result of the strikes, which was welcomed by many liberal sectors in Mexico. The Mexican Liberal Party, founded in 1906 by Ricardo Flores Magón, an anarchist with a radical tendency, took up many of the demands of the people and established himself as the main opponent of the Díaz government.

By late 1910, political turmoil had reached a boil. A prominent Díaz opponent was assassinated in November. This was perhaps the spark that truly ignited the rebellion against the dictator. In May 1911, revolutionaries finalized their seizure of Mexico. Díaz lived in Mexico City then, where he suffered from gum disease, deafness, and exhaustion. He was eighty years old. On May 25, 1911, Díaz resigned. A week later he departed Mexico in a German steamship. He lived and toured various places in Europe, eventually settling in Paris, where he died in 1915, at age eighty-four.

Don Porfirio did anything to hold on to power, often resorting to coercion. However, he also relied heavily on cooptation. For example, instead of posting cabinet members from his own political party, he chose cabinet members from all parties, even those that had traditionally opposed him, and he was able to bribe them with money that he had helped to secure from foreign investments.

He was able to make peace with the Catholic Church and the Freemasons of Mexico because, though he was the head of the Freemasons in Mexico, he was also an important advisor to several Bishops. He gave the church a unique level of autonomy, neither antagonizing the Catholic Church nor ardently supporting them.

Don Porfirio also managed to satisfy Mestizos and even some indigenous leaders by giving them political positions. He then shrewdly made them act as intermediaries for his foreign investment interests so that practically no opposition would fall on his own lap. Instead, they grew wealthier, in effect, folding them into the upper class.

Some have argued that Díaz’s reputation as a despot stems from Revolutionary propaganda. Nevertheless, the facts of history remain untouched. He grabbed power by force when he lost a corrupt election, then he ran on a platform of no reelection. After his first tenure, he later ran for reelection and kept power through corrupt elections. Díaz suppressed the formation of any opposing political parties. He then dissolved all the past vestiges of federalism and the local authorities. Governors answered only to him. The legislative and judicial branch was comprised entirely of his most ardent supporters and closest friends. Díaz suppressed a free press and rigged the judicial system. Virtually in every fashion, congress was simply there to implement his vision for Mexico. It is safe to claim that Don Porfirio ruled by treachery, deceit, ruthlessness, and murder.

*

Now about Little Paris. At the time of the Porfiriato, Tlaxiaco was one of the most important cities in Oaxaca due to its commercial, political, social and cultural significance. The principal reason for this prominence was the existence of craft workshops, where bread, aguardiente, cigars, cigarettes, beer, shoes, hats, silver jewelry, tanned leather, horse tack, soaps, serapes, pulque, and field tools were produced. The products of the workshops attracted mule teamsters, who declared Tlaxiaco an obligatory stop in order to purchase goods for transport to the Pacific coast or to Puebla, Orizaba, and Veracruz.

In 1888, the artisans of Tlaxiaco were invited to an international fair in Paris, where the excellence of their merchandise was quickly recognized, bringing worldwide fame to the town, and euphoria to the citizens. The wealthy families, influenced by this recognition, and strongly promoted by Don Porfirio Díaz, adopted a taste for French culture and fashion. The women wore dresses with large petticoats, scarves, gloves and hats, while the men wore top hats and suits with tails. Consequently, “The Little Paris” became the nickname of Tlaxiaco.

At the beginning of the Mexican Revolution in 1910, the social strata of Little Paris had enormous economic differences. The landowners and merchants were the privileged ones, enjoying a high economic, social and cultural level of life, while the majority lived in misery. Economic and commercial collapse followed the Revolution. Consequently the elite relocated, leaving the city in poverty, delivering the death of Little Paris.

From Oaxaca de Juárez to Little Paris

Our choice for transport from Oaxaca de Juárez to Little Paris was by minibus, a vehicle known as an urban in Oaxaca. The terminal for this small business is located a few blocks from the zócalo in the capital, so we found tickets easily. A Mercedes-Benz urban leaves every half hour, beginning at four in the morning. We paid $7 each. After three hours of travel, we arrived at the tiny Autotransportes de Tlaxiaco terminal. We stepped out of the urban into Mixteca, the most western region of Oaxaca.

Hotel del Portal

Only a short walk is required from the Tlaxiaco urban terminal to the Plaza de la Constitución. Originally known as La Plaza de Armas, this plaza is the heart of the city, the location of the famous El Reloj, the clock, completed in 1947 as the first cement structure in Tlaxiaco, and considered the symbol of the municipality.

We selected the Hotel del Portal as our choice for lodging. Conveniently located on the Plaza de la Constitución, offering a restaurant, bar, and large comfortable rooms for $27. It was an easy choice. Tomasina at the front desk welcomed us and showed us to our room. We could not help noticing the cleanliness and the service staff constantly mopping and wiping.

Strolling Around Little Paris

Little Paris is a small city of about 40,000 mostly indigenous citizens. Anywhere of interest is within easy walking distance of the Plaza de la Constitución. The city is very colorful. Murals adorn the walls along many streets. Flowers and artesania are never out of sight. Calendas, processions featuring costumes, music, dancers, and a festive attitude are common in Little Paris. Quinceañeras, the fifteenth birthday of girls, marking her passage from girlhood to womanhood, occur almost daily, producing ceremoniously dressed assemblages of families and friends leading marching bands, horse parades, riders of chrome bicycles, and decorated pickups to the church.

Little Paris streets are ups and downs, the sidewalks narrow and broken. The big clock at the Plaza rings every hour. Church bells toll constantly. Street dogs are healthy, few destitute people are present, although amputees are common. The people are clean, noble, polite, and welcoming. Mototaxis zip around to carry passengers and purchases. The air carries the scent of flowers, and absent is city exhaust and sewage.

On Saturday morning, trucks arrive bringing farmers to the vast market to sell their fruits, vegetables, breads, wooden furniture, leather craft, pottery, hats, blouses, and, most of all, their woven baskets. Shortly the trucks return to carry away the farmers back to their villages in the surrounding mountains. Street music never stops on Saturday.

Street Food and Restaurants

We are aficianados of street food. Little Paris offers savory tamales, empanadas of spicy squash and roasted chicken, huge tortillas garnished with rich salsas, breads, pastries, ice cream, and creamy fruit malts. Café de olla, cinnamon flavored coffee brewed in a pottery crock, is a morning favorite. Raw food sold on the street includes chiles, garlic, toasted grasshoppers, seeds, nuts, and salty fresh cheese called queso normal.

Restaurants are rare, most serving only comida corrida, the fixed luncheon meal, no menus. Chicken is the usual entré, traditionally smothered with mole negro. Table salsas are almost always orange habanero chiles. Green habaneros are rare, as is chile de arbol, both of these the usual in other parts of Oaxaca. Our chosen comedor was the Soltequita, complete with caged parrots, quail, and turtles roaming free in the garden. The obliging chef prepared us enchiladas verdes de quesillo in fresh cream.

Aguardiente with La Tía at Cava Barra y Café

Mezcal is not distilled in Little Paris. My research had suggested that there is indeed a mezcal called ticunchi. Our searching for this mezcal proved fruitless. We learned that the climate is too cold to grow maguey. Despite being told several times that no such mezcal exists, I continued to stubbornly inquire. Seeing a sign on a building reading Cava, wine cellar, I walked to it and, to my surprise, the door opened at just that moment and a young lady welcomed us in. I do not believe in coincidences. It was certainly no coincidence that I found Cava. Thank you Buddha.

The Cava Barra y Café is a like a softly lit lounge of the 1960s. It reminded me of a coffee house I had visited in Seattle in August 1962 while attending the World Fair there. That coffee house was near the University of Washington. I went there hoping to hear bebop jazz, beat poetry, and hopefully meet Jack Kerouac and Dean Moriarty. I was on the road, about to turn eighteen, so why not?

The Cava offered sofas, sofa chairs, modern jazz, dim lights, a seductive bar, a wall covered with modern art, and a bar shelf filled with various spirits. It was absolutely alien for indigenous Tlaxiaco. The cantinera was Georgina Padilla, dressed in a long fashionable duster. She was elegant, right out of Vogue magazine. The setting was anachronistic, astonishing, and unbelievable, especially for the time and place.

After futile minutes of discussing the sought mezcal ticunchi, Georgina suggested that she introduce us to her Tía, and we accepted. Moments later, a stately, dignified matriarch appeared. Her powerful presence caused me to rise immediately. Our subsequent encounter lasted two hours, almost all spent listening to her teach us about her craft spirits, her bebidas artesanales, and sampling her exquisite elixirs, formulated for enjoyment and to cure the evils of the soul and the body.

Aguardiente is the tonic of Mixteca. This alcoholic drink is distilled from sugar cane. The unknowing might consider it a brandy, or even a rum, but Mixteca aguardiente is not that. In Mixteca it is medicinal and distilled according to what cure is desired. Coyote and Huaco are common remedial aguardientes. Aguardiente coyote is extremely bitter and is more medicinal than enjoyable.

Coyote is an herb that helps treat pelvic problems, such as ovarian cysts, amenorrhea, and menstrual pains. This herb helps during pregnancy, to accelerate it, to help speed up the labor process and facilitate the birth of the baby. Coyote is also used to calm stomach discomfort, to calm pain that occurs with stomach upset, or cramps.

Coyote is also used to eliminate the discomfort caused by receiving the “evil eye” from a witch, such discomfort being fever, headache, vomiting and consistent diarrhea. The intake of this herb also brings relief from sustos, fright attacks, which can cause spasms, nervous states, headaches and back pains. Coyote poultices treat open sores. La Tía claimed that coyote is especially beneficial for calming someone who is angry. Her statement was “para no encabronarse.”

Huaco is used to cause menstruation, to fight fever, and externally to treat rheumatic and bone pain. La Tia said, “It is to use for arthritis caused by cold weather. A shot of this will send warmth to the body after about 5 minutes.”

As for ticunchi, La Tía explained that it is a drink made from maguey papalometi. Pieces of roasted papalometi are traditionally added to aguardiente or mezcal to provide a sweet flavor. La Tía stocked aguardiente ticunchi in her cava. She brought some, we sipped it, found it delicious.

When we first tasted aguardiente ahuu, we exclaimed ooh! La Tía triggered us to laugh when she explained aguardiente ahuu. She told that presidential candidate Lázaro Cárdenas had come to Tlaxiaco in 1934 and had enjoyed the aguardiente. When he first sipped the bebida, he exclaimed ooh, just as we had. But after three sips he elevated his exclamations to ahooh, pronounced in Spanish ahuu. This gave birth to aguardiente ahuu.

In the dim light of dusk, after having absorbed the teachings offered by La Tía, and after enjoying the bebop jazz of hep cats Charlie Parker, Max Roach, Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie, and Thelonious Monk, we left the Cava carrying a case of aguardiente of different flavors. A mototaxi carried our ticunchi sodden bodies to the hotel.

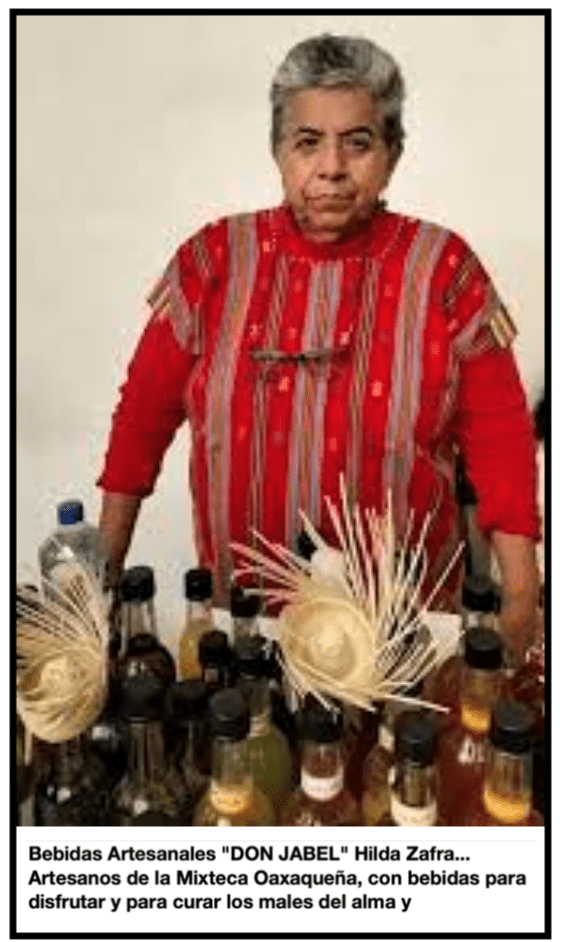

Back home in Oaxaca de Juárez, searching the internet for information provided us by La Tia at the Cava, we found the actual La Tía. Her name is Hilda Zafra. She is famous, known for her Bebidas Artesanales DON JABEL, Artesanos de la Mixteca Oaxaqueña, con bebidas para disfrutar y para curar los males del alma y cuerpo.

We did not see what caused the commotion, but we hurried to see. A man had been stripped naked and detained by the police. Citizens surrounded the villain, many shouting carterista, pick pocket. The police protected the robber from enraged citizens, many of whom had removed their belts and were attempting to whip him.

Feathered Hat

The señorita approached me in the restaurant of the Hotel del Portal. “How old is your bag?” she asked in English. I answered fifty years. She responded, “It has seen many troubles.”

We spoke in English for a bit, while Karen spoke Spanish with her two parents. The three were from Mexico City. They were traveling together because the parents were in their sixties and wanted to travel before they became too old. They had their private car. None had traveled to Oaxaca. Their first stop was in Tlaxiaco, which they found enchanting because of all the fresh food, the opposite of Mexico City, where all the food is packaged. They planned to leave that night, headed to Tlacolula then to Oaxaca de Juárez. Karen informed them of the big market in Tlacolula on Sunday, of which they were unaware.

The señorita wore a hat adorned with many feathers. She compared my bag to her hat. “These bind us together,” she claimed. “Somos almas gemelas.” Hindered spirits. She had traveled to North America, and much of Europe, and also Turkey and Greece. Along the way she collected feathers, one for each country, and stuck the feathers in her hat. She wore a scarf, and the clothes of a traveler, and I admired her, and my senses assured me that she was one of us. She had learned English in school, but had found that her best teachers were travelers, all of whom spoke English, regardless of their nationality. I reminded her that we call it traveler’s English. She smiled and nodded agreement.

When she asked what I liked best about traveling, I answered the exchanging of cultures with the locals. She nodded approval and told that she liked paisaje, the landscape, especially waterfalls. She and her parents had traveled to a waterfall the day before.

All the while I noticed her mother glancing at us. I was reminded of when I had exposed my parents to my Mexico for the first time. Long ago, but still vivid in my memory.

“We saw you in the market,” she told me. I said to my mother, “He is my brother.” My mother did not understand. “His mochitita,” she explained. “He has traveled. He has overcome many obstacles. Troubles, it rhymes with travels. He knows the way. It is his mochilita that reveals him. It exposes him as one of the road. I have not seen a mochitita so worn as his. He must be very old, but very young. His compañera also knows the way. She is the same as him. Look at her native clothes, and her hat. That pair are cuates. Both of those two are true. They wear the glow. My mother could not see it, but she could hear it, and she knew that I spoke from my soul. My mother saw for the first time why I go.”

She stood straight, firm, and solid, this senorita, and I knew that she would have been with us on any ride to the First Time. She was a seeker of First Times, the same as Karen and me. Those are the treasures, of course, the First Times. How old must you be to know that?

Chatting with Locals

Being the only white faces in Little Paris, the locals considered us curiosities and seized the opportunity to speak with us. The young lady selling coffee and bread on the street in the mornings surprised us by speaking English to us. “Where did she learn? In school. Do you get many chances to speak English here in Little Paris? Very few. Not many tourists come here? You are the first in a long time.”

In the comedor watching the World Cup, an older man came to our table to ask about us. We learned that he was from Sonora, in the north of Mexico, that he was visiting relatives in Oaxaca. His answer as to how he liked Oaxaca was revealing. “In Oaxaca the young help the old, give them a hand, help them. Not so in Sonora. In Oaxaca the young address the old in the usted form, the formal you, the you of respect. In Sonora the young address the old in the tú form, the informal you, the one used for intimate friendships, children, and inferiors.” We nodded in agreement, adding that the children in Oaxaca, no matter their age, always address their parents in usted.

He observed, “I hear that you use usted, never tú. Why is that?” Our answer was that we learned Spanish on the street, that we were always addressed usted, and we returned the respect. He laughed. “That’s because you are white. If you were morena, the street would call you tú.” We laughed at yet another example of white privilege.

A well-dressed man approached us in the market. Without hesitation he asked in English, “Where are you from?” We answered USA. “Where?” New Mexico. “I lived in the United States for nearly twenty years. Legally.” We told him that we live in Oaxaca de Juárez. Legally. “¡A poco! Wow! Why?” We like Mexico and can live anywhere we want. “Did you leave the States intentionally? Because you didn’t like it?” We shook our heads. He continued, “I left intentionally. When I first went there, I liked it a lot. The land of the free, the home of the brave. I liked that saying. But that changed. Now it is tierra de odio, hogar del arma. Land of hate, home of the gun.” We could not resist a despondent hollow laugh. He grinned. “Como los de más,” he concluded.

We asked what he did in the States. “I got my undergraduate in chemical engineering at the University of Colorado. My MBA at Booth. After graduate school in Chicago, I went to Dallas and worked in finance with Goldman.” We nodded in appreciation of his accomplishments. He acknowledged by continuing to speak. “At Booth I learned the concept of doing business in the States. Americans are driven by two fears. Fear of a changing culture, and fear of not having enough money. Business success depends upon how well one preys upon those fears. Goldman sells the concept that the minorities are taking over, so you better invest before they get all your money. That’s easy to sell in Texas.” We laughed, and so did he, but we knew he had a good point.

He asked, “What do like best about Oaxaca?” Our answer was immediate. La buena onda. He erupted in a huge smile of agreement. “Yes, the good vibes the people put out!” We all stood still as our chance encounter closed. “Que le vaya bien,” he wished us, offering a hand sign of respect while walking away.

The Triquis

Long, red, woven robes called huipiles are emblematic of the colorful ethnic population of Mixteca. We being costume collectors, this traje attracted us from the very first hours of our very first day in Oaxaca. Indeed, it was our search for these red robes that took us to Tlaxiaco for the first time, as the Triqui go there for the weekly Saturday market.

After living only shortly in Oaxaca de Juárez, we quickly saw that Triquis are ever present in the capital. Their presence is always associated with social protests. They have a permanent protest in the zócalo in front of the Palacio de Gobierno, and frequently march in the streets to support not only their own community interests, but those of any groups that are struggling.

The Mixtec language region is inhabited by the Mixteca culture, born about 1500 BC. Because of the mountainous terrain, communications with other parts of Mexico are difficult, consequently, the region is poor, remote, and seldom visited. The name Mixteca means “cloud people.” Until conquered by the Spanish, the Mixtec allied with the Zapotec kingdom of the Central Valley. They made major constructions at Monte Alban, eventually gaining control of it. They were considered the foremost goldsmiths of Mesoamerica, utilizing lost-wax casting.

The pre-Contact Triqui constituted an agrarian community. One community occupied high, cold, misty mountains that were not inviting to Spanish invaders. Highland crops included corn, beans, chilies, and squashes, produced almost exclusively for local consumption.

Fortunately, another Triqui community occupied the lowlands, which provided excellent land for the cultivation of coffee. The export of these beans outside the Triqui area instigated acculturation of the Triqui into neighboring mestizo populations. Cultivation of sugarcane, bananas, pineapples, oranges, and mangoes also provided produce to be sold to mestizo communities. Additional products to sell to mestizo buyers were huipiles, shirts, belts, palm hats, and palm baskets.

The main Triqui religious ceremony is the festival for the God of Lightning on 25th April. It is held within caves called the House of Lightning. The ritual joins many symbols around the figure of the Feathered Serpent Quezalcoatl. A live goat is brought into the cave by one of the principales. Uttering prayers in Mixtec, he offers the goat to the God of Lightning, and at the same time he makes a deep cut in the goat’s neck, from which a stream of blood gushes out, bathing the place in blood. The Triqui believe that blood is a petition for water, alluding to the rains for which they are asking. Afterwards, the goat’s meat is distributed among the participants. Despite intensive attempts at evangelism, this tradition continues.

The Movie Star

All over Tlaxiaco are photographs of Yalitza Aparicio, a native of Little Paris who became a superstar actress because of her role in the 2018 Oscar-winning film “Roma.” Yalitza was nominated for an Oscar for best actress in that film. While featured on the covers of Vogue Mexico and Vanity Fair, she also became a lightning rod for discussions of race. She was teased by comedians and targeted by bigots who used racial slurs when referring to her. Nevertheless, Mexicans of all social classes acknowledged that a moment of change had arrived when an indigenous woman received so much focus. While I was admiring a photograph of Yalitza in a store window, a Triqui señora paused beside me and remarked, “When I was growing up and watching television, I never saw faces that looked like mine.”

There were several photographs of Yalitza in the Restaurante Antojo. Noticing our interest in them, the Mixtec owner unexpectedly approached us, and we talked about race. “You know,” she offered, “we all have tears that are the same color, as is our blood and our sweat. Our only difference is skin color. But it is the skin that brings all the trouble and pain. My baby girl was super white. I was worried that people would think I stole her. Some of my friends told me that I was lucky to have a white baby. They had unsuccessfully tried to change their children’s complexion with skin-lightening products. It is common for parents and grandparents to advise young people to find a light-skinned partner to ensure better opportunities for their children.

“Everyone knows that darker-skinned people earn less money and have fewer educational chances. Racial inequality is obvious in our society, where women employed in cooking, cleaning and babysitting are almost always dark-skinned. Within families and friendships, the lighter-colored person is often nicknamed güerito, or blanquito, and those with darker skin are called negrito or morenito. The word indio is commonly used to describe someone who is lazy. When one sees a sign that reads “Servant Wanted,” only dark-skinned people apply.

“The rubios are to blame for this racism in Mexico. Those blondes established our caste system in which social position is determined by race. At the top are those of European descent, followed by those of colonial and indigenous high heritage, then come the aboriginal people, followed by the very bottom, the black slaves.

“Curiously, it is difficult to get light-skinned people to recognize that Mexico is stratified by skin tone. These güeros still believe the myth that all Mexicans are mestizos, a single mixed race of indigenous and Spanish blood. And these burros insist that there is no prejudice here because all Mexicans are the same. They continue to believe this, even when I point to the whitexicans, that word for Mexico’s wealthy, light-skinned elite. You know, the privileged members of the pigmentocracy, that social order in which skin color is the single most important determinant of a person’s economic and educational achievement.

“¡Ni modo! You might as well argue with a mirror as argue with each other. After all, aren’t we all really the same person? The same blood runs in every human on earth. You just have to see past the variations in skin and culture.”

The señora’s openness and frankness was stark and sharp in comparison to the usually quiet, soft spoken Mexican who hides his opinions.

The United Nations

It was our last night in Little Paris. We decided to celebrate at the Café Colón, our preferred nocturnal hangout. Waiter Diego whom we had befriended, and whom we called Deko, served us with a smile and a mope of sadness to learn that it was our last time there. “¿Aguardiente ticunchi?” Deko asked. We nodded a yes at him.

We had not really paid any attention to a fellow sitting alone nearby, but suddenly he stood beside our table. “Buenas noches,” he greeted us. We responded in kind. “Veo que se están divirtiendo. ¿Primera vez en Tlaxiaco?” I see that you are enjoying yourselves. First time in Tlaxiaco? We shook our heads and answered it was our second time. “Que feliz,” he smiled. How happy. Then to our surprise, he said in perfect, unaccented American English. “Would you mind if I joined you? We could chat a bit. You know, shoot the bull. I don’t get a chance to hob-nob much with Americans.” We laughed and welcomed him into a chair, noticing that he carried a caballito in his left hand, and that it breathed the perfume of ticunchi.

The three of us nattered for several hours, parting only after Deko had finished cleaning and was ready to turn off the lights. Ralph had been born Rafael in Puebla thirty years previous. He was taken to Alexandria, Virginia by his adinerado parents when he was six years old. He had attended public school in Virginia, and then Exeter Academy before attending Duke University, where he graduated with a degree in physics. He had lived in Mexico during summers. After college, he had “walked about” Europe and Asia Minor, which he called Anatolia, for a year before moving permanently to Geneva, Switzerland, there being employed as a conciliator by the Human Rights Council of the United Nations.

Ralph had been in Mixteca for several months , his purpose to serve as an interface between the Mixtecas and the Guerreros Unidos cartel, in hopes of avoiding another incident like the murders of the more than forty Ayotzinapa College students in 2014. That state sponsored killing, at the orders of the Iguala, Guerrero mayor, carried out by the Mexican military, facilitated by the Guerrero cartel, remains a hot-button issue in this part of Mexico. Ralph’s role as an arbitrator fit the answer that he gave when we had asked how a physicist became a humanitarian, as he had responded that his travels had convinced him that “Adam’s are more important than atoms.”

Musing over a kiss of ticunchi, Ralph commented, “You must like it here in Oaxaca? When were you last in the States?”

Karen offered me the stage by kissing her caballito, so I replied by describing our lifestyle. “Well, our most recent visit to El Norte was in 2015, and that was only to El Paso, Texas. Actually, no reason to go north. My driver’s license is expired. I don’t need one. And I can renew my passport from here. We have permanent Mexican residence visas and an RFC, the Mexican federal tax ID, you know, a cédula. We have a non-expiring rental contract, so we are secure with a place to live. Medical and dental service here is more than adequate. Our exclusive neighborhood is safe. A produce market, a dairy store, and a bakery are just a block from our house. We have an internet – telephone – television package. Amazon and FedEx come to our door. We have personal drivers on call, and a gardener and gatekeeper. Our housekeeper of a half-dozen years is essentially a family member. We got her a passport so that she can accompany Karen on trips outside of Mexico. All the chefs at our restaurants know what we like. Our central valley mezcal is privately distilled from the best wild maguey. We have more friends here than we have in the States. ¿Que más le busca?”

Ralph stared at me and declared, “Then you never lived in the United States when Trump was president! Nor since.” I nodded to affirm. “¡A poco!” he exclaimed. “The USA is not the country you left, you know.”

I shrugged. “Muy bien, Ralph. I’ll share a story with you. Just after Trump was elected, one night we sat at the Importadora on the zócalo in the capital. We had stayed later than usual. The only ones left in the zoc were the sweepers with their long brush brooms, and it was quiet, and we could hear the swishing, so rare that we lingered to listen. A female traveler sat alone several tables away, her backpack propped against a chair. Our eyes met, and when we smiled at her, she said ‘Good evening. Nice and peaceful.’ We nodded and asked if she would like to sit with us, and she did.

She was German, spoke four languages, Spanish her weakest. We spoke traveler’s English with her. She had traveled through the United States to reach Oaxaca, had spent a month in Houston, Texas. She chuckled about Texas English. “They speak with a strong accent, and I had to learn to understand them, like I did when George Bush was president.” We laughed with her. She felt comfortable enough to speak openly. “Houston is very international, but the rest of Texas is… well.” She used two hands to mimic cowboys shooting guns. And then she moved her arm far to her right side and remarked, “They are way over there.” We laughed some more.

“I liked Houston,” she smiled. “All those young people with their thrill for life.” Then she dropped her smile and almost cried. “Do they not know what they have done? Trump of course. It will take generations to repair the damage he will do. Europeans are concerned. We have always looked to America for its strength through its remarkable Constitution, unequaled and respected by all Europeans. We fear that you have voted it away.” She paused and stared into the zoc before continuing. “I am especially concerned about Russia, as is all of Europe. Trump and Putin are twins.”

Ralph sat still all the while I recounted the story. “Bueno Ralph, I recall vividly that platica with the German traveler. But ya chole about American politics.”

Ralph’s nodding head exposed him as agreeable to change the subject, and he did. “What about your music? What kind do you like?” We answered that we like all kinds, particularly trova and corridos.

When we asked what he liked, he became animated and enthusiastic, exposing that his knowledge of music was expansive and all-inclusive. He especially liked bulería, that fast, cheerful, boisterous flamenco rhythm always accompanied by hand clapping and the clapping of heels of the flamenco dancers. Deko heard that, so he found some bulería to entertain us, earning applause from Ralph, who enjoyed the bulería while flaunting happy pantomimes of a dancer. Suddenly he laughed and shouted in joy, “Jugaremos en el bosque mientras el lobo no esta.” We will play in the forest while the wolves aren’t there. That caught me by surprise as it seemed out of time and place, but after the music died and our festive moods morphed to the contemplative, I began to understand.

Naturally our substantive conversation included social and political aspects of not only Mexico, but of the world. Being that all of us had traveled, we had many experiences from which to draw our opinions and observations. At appropriate times we spoke Spanish, but mostly American English. His American slang dwarfed anything that we could contribute.

Ralph was especially intrigued by our experiences walking in the wilds – interested that we had no map, no compass, just went, asking for guidance from locals along the way. He asked, “Were you ever afraid when you were out there alone on those walks?”

I answered, “Not at all. You mentioned playing in the forest when the wolves aren’t there. Well, we slept with the wolves without fear. The wolves knew that a lion was amongst them.” That brought laughter from Ralph.

Of course we were keenly interested in Ralph’s experiences with the cartels. He was reluctant to disclose much color, as he considered it sensationalism, claiming that we could learn all that from the histrionic Mexican newspapers. Ralph asserted that the cartels know that if you want to control someone, all you have to do is to make them feel afraid. He believed that to escape fear, you have to go through it, not around it. He described his task as teaching the community how to surmount fear.

Ralph declared that the dominant psychological impact of the cartels on the fearful villagers is to bolster their resolve to remain silent about anything that the cartels did. Snitching resulted in death to body and family, so Ralph had trouble getting anyone to admit to anything or to provide any information. His medium of explanation employed a 17th century theater presentation. We listened eagerly as he described the play.

Fuenteovejuna is a three-act drama written by Lope de Vega in 1610 and published for the first time in 1619. The play is based upon a historical incident that took place in the village of Fuenteovejuna in Castile in 1476. The main storyline is the uprising of the people, who want justice because the village commander, assigned by royalty, abused his power. The play was frequently adapted by communist powers during the 20th century in order to display the message of the power of the common people over the aristocracy.

Women’s rights is also a major theme in the drama, a most unusual concept for the time of that writing. In 1610, women vassals were subject to droit du seigneur (‘lord’s right’), also known as ius primae noctis (‘right of the first night’). In medieval Europe, this was segunda-ley (second law, unspoken and colloquial, but tolerated by authorities, especially in a local town). It allowed feudal lords to have sexual relations with subordinate women, especially on the wedding nights of the women. In practice, it allowed the feudal lords to use their power and influence over serfs to sexually exploit the women free of consequences, as opposed to an actual legitimate legal right.

During the first act of the play, the commander attempts to take two women to his castle, but they resist and escape. Later, two young lovers meet in the forest, where the commander finds them. When the commander puts down his crossbow in order to force himself on the woman, her lover grabs it and points the weapon at the commander. The woman escapes the commander, and the two flee as the commander curses them and threatens revenge.

The second act begins with the commander demanding that the father of the desired woman allow him to have his daughter. The father refuses, which the commander considers an insult and insubordination. Later, the desired woman and one of her friends, accompanied by a shepherd, go on a walk, where they are approached by a third woman, who is being chased by the commander and his servants. The shepherd attempts to protect the chased woman, but he is beaten by the commander’s lackeys while the commander rapes the pursued woman before turning her over to his men for more raping. The second act ends with the commander arresting the man who had pointed his crossbow at him.

Act three opens with the desired woman appearing while the village men are discussing what to do about the commander, who is preparing to hang the imprisoned man. The men do not recognize the woman because she has been beaten by the commander when she again fought off his advances. The desired woman complains that the men did not try to rescue her. Dishonored by the accusations, a band of men kill the commander. One of his servants escapes and flees to report to royalty. Because the assassination was not just murder, but also mutiny against the crown, the shocked rulers ordered a magistrate to investigate.

The arrival of the magistrate in Fuenteovejuna brings the climax of the drama. The villagers are celebrating with the head of the commander on a pole. In order to save themselves, they all say “Fuenteovejuna lo hizo.” (Fuenteovejuna did it.) Even as the magistrate tortures the villagers, they continue their claim. The magistrate capitulates and retreats to royalty, where the rulers also concede defeat and pardon the villagers. The refrain Fuenteovejuna lo hizo became a tag line that subsequently appears over and over in Spanish language literature and speech, meaning “it’s nobody’s fault,” or perhaps better expressed, “you’ll have to punish all or none of us because this was a collective decision.”

Fuenteovejuna rules Mixteca. Ralph emphasized it in yet another way. “Alexandre Dumas must have known about Mixteca when the wrote The Three Musketeers. Like those three gentlemen, the Mixteca motto is “All for one and one for all.” Fuenteovejuna is exactly that.

A lingering pause surrounded our table. Changing the pensive mood, I asked Ralph if he had a one-word descriptor for the cartels. Waving his forefinger with decisive authority, he quickly answered: territorial. That response served to open a discussion of tribalism and aggression. All of us had studied three principal authorities: Robert Ardrey, Konrad Lorenz, and José Ortega y Gassett, and we mentioned them throughout our platica. Ralph had read Lorenz in the original German, but we two Americans had read only the English translation of Lorenz.

Ralph poked fun at us about the line in the Quentin Tarantino movie Inglorious Basterds, and the scene when Bridget Von Hammersmark asked, “I know this is a really silly question before I ask it, but can you Americans speak any other language other than English?” We quipped that such an American would be an immigrant. All of us laughed.

We delayed our discussion on tribalism to speak about our Spanish. We told Ralph that we described our Spanish as “learned on the street.” We told him we spoke español callejero, street Spanish, using callejero for street, which truly means a stray dog that lives on the street. “Hablamos como callejeros,” we claimed. Ralph laughed heartily at that disparaging pronouncement. “No es,” he said. “Conjugan verbos.” No you don’t. You conjugate verbs.

Ralph added, “Obviously you are formally educated. But you also know the street. Way better than I do. I envy you for that. Too much education often makes one numb to the obvious, especially if one’s education is with those of the same cultural class, like mine. Diversity is essential, and I didn’t experience it. Such an education as mine, with all of us students from the elite class, unfortunately builds fences. Fences are built on fear. People fear people who are smarter or different than they are.”

We nodded. I asserted, “It’s easier to build fear than to build a wall.”

Karen laughed and said, “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down that wall.”

Ralph laughed loudly. “Mr. Trump, stop that wall!” We all laughed.

Taking a short breath, Ralph continued. “The privileged, like me, but especially my parents, fear people who might seize their property or threaten their position in society. Xenophobia, you know. The elite, the privileged, they love cops because cops are the guardians of the property owners. The callejeros, who own no property, hate them. Do you two callejeros hate cops?”

We laughed. “Pues no, somos de los blancos privilegiados.” Of course not, we are privileged whites. That brought hearty hilarity and an expression of puzzlement to Ralph’s face.

Karen asked, “Why do you think we own no property?” Ralph hesitated and drooped his head slightly.

“That’s a good one,” he answered. “My assumption. My bad. Estoy arrepentido. Tell me.”

“Too personal!” I laughed. “The short answer is that we are of the ownership class. Enough said.”

We saw Ralph exhale. “¿Otros besitos?” We nodded the affirmative. Ralph motioned to Deko. I pardoned myself to visit the sanitario.

Deko had arrived with our ticunchis by the time I returned. Karen and Ralph waited until I sat, then we all toasted and sipped. Karen lifted her caballito. “Here’s to friends and family who know us well, but love us just the same. ¡Salud!” Ralph raised his jigger. Que el camino se levante para encontrarte en tu viaje. May the road rise up to meet you on your journey. ¡Salud!” I lifted my little horse into the air. “May we never go to hell but always be on the way, and may all our ups and downs be under the covers. ¡Salud!”

Laughter died, and sips and soft silence came and went. Ultimately Ralph returned us to discourse of substance. “Now about those tribes. What say you, Paco?”

Wetting my tongue with a kiss of ticunchi, I opened with the assertion that overland travel like Karen and me had enjoyed in the 1970s and early 80s is impossible now. Tight borders, problematic visas, and political issues restrict access to many places. These impediments are the same as fences with locked gates. I named Nicaragua, Iran, and Afghanistan, and I pointed out that Europe attempted to ensure free movement of people, goods, services, and capital when they created the European Union in 1993. The Europeans abolished passport requirements and standardized currency by creating the euro. “Success or the lack of is argumentative,” I proposed.

“Lack of,” chimed in Ralph. “The gravest EU failure is that the livelihoods of citizens of most Eurozone members are being compromised for the benefit of the unelected European bureaucracy. This is possible, and should have been predictable, because the Union was built on Machiavellian principles that prioritize the desires of the most powerful members, specifically Brussels and Berlin. The EU founders forgot that humanity is tribal. Tribalism demands territory. Tribalism is purely Darwinian. Tribalism demands patriotism.”

Karen lifted her caballito to that. “Mankind, especially those male members, are driven by genetic instincts, you know, testosterone, to acquire land and defend territory. Lorenz claimed that all male animals are biologically programed to fight over resources as a principal constituent of natural selection. That primal instinct evolved from a genetic to an inherited instinct. And what resulted from those instincts? The need to develop weapons. Fences are weapons. A man builds a fence. Then he puts a dog behind it. The dog barks warnings at you, expressing the very motive that caused the man to build his fence. Property ownership and nation building require borders and border guards.”

Our platica lulled while we kissed our ticunchi. Ralph interrupted the silence. “Stanley Kubrick. We all know his films. One of my associates in Geneva, a Dane, told me that Kubrick was inspired to produce his 2001 Space Odyssey and his Clockwork Orange films by Robert Ardrey’s books.” Silence again smothered our table. For my part, I would have to contemplate that at a later time.

“We have all read José Ortega y Gassett,” I reminded the table, and all nodded. “For me, one of the most compelling points he proposed is that the quarry is the factor that defines and delineates the hunt. Lacking a formidable quarry, the hunt is diminished. Gassett argues that an inferior quarry results in something other than a hunt.” Nods around the table. “Well, for Man, the most predatory hunter of all, the preeminent quarry is territory. Most all noteworthy battles were driven by the desire for more territory. The Sanskrit word for war translates as the desire for more cows. Here in Oaxaca, the conflicts are between agrarian adversaries, fights over farmland. Mexican cartels fight for economic control of territory. The western democracies fight over territory that protects them – they fight out of fear of being invaded economically or physically. But in the end all of them fight over money, right?” More nods.

A lingering silence of contemplation accompanied kisses of aguardiente. I remarked in summary. “The omnipresent companion of the desire for territory is aggression.”

Ralph nibbled his lower lip momentarily before saying, “Agreed, but not accepted.” Karen nodded in accord, and I joined them. At the same time I noticed that all our caballitos sat empty. A wave to Deko brought otros besitos más.

Our lips sweetened by fresh kisses of ticunchi, we enjoyed a serene moment. Karen pointed to fireflies glowing in the darkness above the patio of the café. Deko moved from the bar to a nearby table, taking a seat to listen to our English.

Wanting to change the mood, I asked, “Ralph, are you and your parents United States citizens? USA passports?” He nodded the affirmative. “What did your parents call themselves before they became naturalized citizens?” That caught him off guard and he had no quick answer, so I added, “Mexicans? Americans?”

After considerable thought he answered, “Immigrants.” Then he asked us, “What do you call yourselves as Americans living in Oaxaca? Expats?”

We two Americans laughed and shook our heads. “No way. Expat is a racist, classist word.” Ralph cocked his head to express that he was puzzled by that response, so I explained myself. “Okay, before they became citizens, your parents had it technically correct. An immigrant is a person who lives permanently in a country outside of their native country. An expatriate, commonly called an expat, is also a person who resides outside their native country. But there’s a difference. In common usage, expat usually refers to educated professionals, skilled workers, artists, or retirees who live outside their native country. Your parents are these, so they should be expats, right? But they didn’t call themselves expats you claim.

“Nor did they call themselves migrants. What makes one person an expat, another an immigrant, and another a migrant? The term expat is used to describe a privileged class living abroad, while those in less favored positions, like construction workers and housekeepers, are deemed foreign workers or migrant workers. So why didn’t your privileged parents call themselves expats? Because they aren’t white. Expat is used exclusively for western white people living or working abroad. Africans, Arabs, Asians, Latin Americans are all immigrants. Americans, Canadians, Aussies, white people you know, are expats because white people claim that other ethnicities can’t be at the same level as whites. Whites are superior, you know. Just ask any Brit or Aussie, or especially any American redneck. Immigrant is a term set aside for so-called inferior races. Most white people, you know, deny that they enjoy the privileges of a racist system. And why not deny it? The white man’s role is to prolong an outdated supremacist ideology. Now do you understand why we don’t call ourselves expats?”

Ralph leaned back in his chair and sighed. “¡A poco!” I’ll have to speak with my parents about this. Never thought of it that way.” We nodded at him and let silence sit with us a bit.

A kiss of ticunchi before continuing. “Another thing, mi carnal,” I motioned to Ralph. “That patriotism thing.” Ralph raised his eyebrows and Karen kissed her caballito. Then I started. “These thoughts arise from my travels and my exchanges with foreigners, many of whom share my opinions. That said, I view patriotism as nationalism, and I conclude that it always leads to war. Patriotism is the egg from which wars are hatched. Patriots always talk of dying for their country, but never of killing for their country. Patriotism is mostly pride, and definitely combativeness. Patriotism always has a chip on its shoulder. Every fool who has nothing at all of which he can be proud, adopts as a last resort pride in the nation to which he belongs, even though he didn’t choose where he was born, and where he was born didn’t choose him either.”

Ralph was clearly interested. He had leaned forward and his right elbow rested on the table edge. After another caballito kiss I persisted. “Bully patriots, those ones too set in their ways or too poorly educated, or both, to get beyond the ceaseless flag-waving and nationalistic bluster, always spout that lie about the American Dream. But these patriotism purveyors have it wrong. It’s called the American dream because you have to be asleep to believe it! America, land of supermarkets and superhighways, of supersonic jets and Superman, of supercarriers and the Super Bowl. Was there ever a country that coined so many super terms? The patriotism purveyors use patriotism to lock every nation of the world into a full nelson and make it cry Uncle Sam!

“You know that old adage. Patriotism is the last refuge to which a scoundrel clings. But it’s more than that. Patriotism is a superstition created and maintained through lies and myths. In every age it’s been the tyrant, the oppressor, and the exploiter who has wrapped himself in the cloak of patriotism to deceive his people. Purveyors of patriotism know that if you steal only a little, they throw you in jail. But if you steal a lot, they make you king. Those same purveyors know that most of the world is composed of slave camps, where citizens, truly just tax livestock, labor under the rule of patriotism mongers. You’ll never have a quiet world until you knock the patriotism out of the human race.”

Ralph stared at me, then at Karen, and then at Deko. After the lull had expired, I remarked, “Maybe one more thing about patriotism. Actually two more things. In the early 1970s Karen and I drove my sportscar to Panamá. The Thatcher Ferry Bridge spans the Panamá Canal where the PanAm highway crosses the canal into Panamá City. Now that bridge is called the Bridge of the Americas. When we crossed, there was a huge American flag right at the bridge because the United States still owned the canal. Karen said that her heart soared when she saw those stars and stripes after having been away from the United States for weeks. Patriotism you know. Karen had it at age twenty, before she had traveled.

“In 2014, a young lady age twenty accompanied us on a long trip into Mexico. It was her first time out of the USA. Our return to the States was through Juárez and into El Paso, Texas. While driving to our hotel, she saw an American flag blowing in the wind. She announced how that thrilled her, and she asked if we felt that way. We professed that we did not. Karen disclosed that she had at one time felt patriotism, but that after crossing so many borders, knowing so many cultures, that the emotion called patriotism had melted.” I stared at Ralph, “Now, what say you mi carnal?”

Ralph did not blink when his unexpected reply ignored my question. “Paco, do you ever feel ill?” That surprised me, but I answered without thought because my answer came naturally. “Don’t be ill. Life is too short to be anything but happy. So kiss slowly. Love deeply. Forgive quickly. Take chances and never have regrets. Forget the past, but remember what it taught you. Maybe most important of all, know that audentes fortuna iuvat, fortune favors the bold, la fortuna favorece a los audaces.” Ralph smiled and pointed his finger at me.

After several kisses, Ralph spoke softly. “I’m feeling quite healthy just now. You know what? Illness disappears when stillness consumes you. The meanest enemy of your life is your own mind if you don’t know how to keep it still. Stilling the mind is the extremely difficult task of ignoring the past and the future. Success at that leaves only the now. One of my past girlfriends told me that life is life and fun is fun, but it’s all so quiet when the goldfish die. I’ve never understood that, but I have no doubt that she was right. She was right about a lot of things.

“Yesterday I woke up feeling ill. So I took the first bus away from town, away from noise and people. I got off the bus when I couldn’t see anybody or any houses. I walked downhill for a while until I heard running water, and I went to it. Those places are the most peaceful I know. There I sat and stayed the whole day, with both nothing and everything on my mind, cleaning my head. Stillness, and her companion Silence, I learned long ago, are often the most beautiful couple.”

Ralph mused silently and glanced at the fireflies before continuing. “When I meet with my rebaño, my flock of protégés, and I am bombarded with questions, forced to make decisions, I always ask myself: What will happen if I say nothing? Sometimes I don’t like having to explain it to them, so I just shut up and stare at nothing. On the other hand, I know that sometimes being silent is to lie. One will win if one has enough brute force. But one will not convince others with brute force alone. To convince others, one needs to persuade. To persuade one needs reason and right, moral right. It doesn’t matter whether you follow science, or whether you follow the Bible, fact or faith, what matters is how you behave with the everyday ordinary people around you. Persuade by example. The unfortunate problem with that creed is that the universe runs on the principle that the one who can exert the cruelest evil on others runs the show. Might makes right in Mixteca. Probably does everywhere.”

Ralph paused to again stare up at the fireflies, kissing his ticunchi. His pessimistic fatalism surprised me, but his candor did not. Abruptly he continued. “You laughed a moment ago about being privileged whites. You concede that white privilege exists, right?” We nodded. Ralph chuckled and waved his arm. “No doubt. I’m white enough to get the privilege, especially here in Mexico.” Ralph grinned at us. “White begets money. Right?” We offered him puzzled expressions. “OK. Put the face of one of your American politicians in your mind. Doesn’t matter which one. This is what all of them would know. ‘If you can convince the lowest white man he’s better than the best colored man, he won’t notice you’re picking his pocket. Hell, give him somebody to look down on, and he’ll empty his pockets for you.’” We all laughed at that, but it was sad laughter, stained with sorrow and shame.

That sad awareness caused me to glance toward the sky. I could swear that the fireflies stilled and ceased to blink. But, of course, that was just me and the ticunchi.

I stared directly at Ralph. “You mentioned feeling ill, Ralph.” He nodded toward me. “I sensed that your illness was not physical.” He nodded again. “Just putting myself in your place, I’d be a tad uncomfortable about what might be coming up behind me.” Another nod from Ralph.

“I keep that thought at bay,” he confessed. A mournful pause lingered around the table before Ralph spoke again. “Here in Mixteca there is a dicho común, a common saying. ‘Los viejos tienen la muerte, y los jóvenes el amor, y la muerte viene una sola vez y el amor muchas.’ The old have death and the young have love, and death comes just once, and love many times. I heed that sagacity daily.”

Staring quizzically at us, he asked, “You know how I do that?” We shook our heads. “I avoid acquisition. My house is empty. No things there to keep me, no things to give away, no things to remember. Why? Because it is best that as one senses a shortness of life that he strip himself of possessions, to shed himself downward like a tree, to be wholly earthlike before he dies.”

We being very acquisitive people, especially of art, we had to let that sink in, so we took lingering kisses of ticunchi for a bit. We waited for Ralph to speak again. We waited quite a while before he almost whispered. “Some of my flock claim that I’m a hero for what I’m doing. That’s wrong. The real heroes aren’t people doing things. The real heroes are the people noticing things, paying attention. Great stories are not the ones which have great people in them. Great stories are the ones which feature ordinary people, willing to do great things, because they take notice of what needs to be done.

“Some of my colleagues in Brussels speak to me about this. They cite the old lie about the good die young. Pura porquería. The tragedy of life is not that the good die young, but that the young grow old and mean. That will not happen to me.” Ralph chuckled and sipped. “Most people die at twenty-five and aren’t buried until they’re seventy-five. Death is not a tragedy to the one who dies. The tragedy is to have wasted one’s life before death. Funerals are not really for the dead. They are for those left behind. The dead are long gone by the time a funeral is held.” Ralph sipped again. “Life is stressful. That’s why they say ‘rest in peace.’” Ralph turned his head toward the fireflies and our table became a silent stone.

The morose mood was not what I wanted for my last night in Little Paris. I laughed to break the sardonic sulk. “OK Ralph, but I’m planning on getting to Heaven. You know, Heaven is the place where all the dogs you’ve ever loved come to greet you.” Our stone table melted into laughter. Even Deko understood and rose quickly to smile at us before heading to the bar.

Every traveler knows when it’s time to go. That moment had arrived. Deko had the floor mopped and the caballitos washed and stacked and the fireflies had disappeared. We three sippers had succumbed to silence. Ralph rose first, moved beside Karen and kissed her gently on the cheek. I rose to stand with him. A hearty abrazo brought us together. Then a long silent standing staring at each other.

Upon departure we shared a hopeful adiós. “See you around mi carnal,” I said.

Ralph shook his head. “’Fraid not. In the morning to Copala.”

“Safe travels,” we wished him, adding “Cuidese mucho. You are around people who comen santos pero cagan diablos.” The ones who eat saints, but shit devils. Those ones who go to church and pretend to be saints, but after leaving the church they commit the vilest of sins.

Ralph waved us away with a not-to-worry smile and repeated what he had first said while the bulería played. “Jugaremos en el bosque mientras el lobo no esta.” We will play in the forest while the wolves aren’t there. Then he extended his hand toward us and wiggled his fingers up and down. Uy qué miedo, mira como estoy temblando. Oh fear, look how I’m shaking. His Chico Che impersonation.

I grinned, but uneasily. I trust my instincts more than my intellect, and somehow I felt edgy when I should have felt jubilant after such a fine evening. Karen and I strolled over a quiet, dark, empty, cobblestone street back to our hotel, me noticing that I held Karen’s hand tightly in mine.

The Massacre

About a month after returning to Oaxaca de Juárez from Little Paris, our trusted driver René was carrying us on a buying trip, and we took the opportunity to tell him about our travels to Mixteca. René surprised us by reporting that a massacre had recently occurred there. That kindled our interest, so we searched newspapers to know more.

We learned that the massacre had occurred in Santiago Juxtlahuaca, a municipality near Tlaxiaco, at a town meeting designed to update Mixteca vigilante peace groups on efforts to prevent the Díaz-Parada gang, a small, insignificant local criminal gang, from obtaining the support of the Guerreros Unidos, a strong cartel centered in the neighboring state of Guerrero. When we read Guerreros Unidos we remembered Ralph.

As is the custom of cartels, a video of the massacre was released to the public for the purpose of instilling fear. The Tequileros, an almost extinct cartel which had been chased out of the area by the vigilantes, took credit for the attack, asserting that it was provoked by a dispute over territory and access. The video exhibited poor lighting, poor sound, and shadowy figures, unlike the professionally-produced, optically sharp videos typical of cartels, which clearly show the masked faces of well-armed killers.

Several days after the massacre, a second video, this one expertly produced, was released by Pedro Díaz Parada and his brother Eugenio Jesús, capos of the Díaz-Parada gang. They declared that the attack by the Tequileros was to kill Pedro and Jesús. Fortunately for them, they claimed, the Tequileros opened fire before Pedro and Jesús got out of their bulletproof vehicle.

The inferior quality of the Tequilero video convinced the Federales that it was fake. Moreover, they did not believe the story of Pedro and Jesús. These concerns caused the Federales to be suspicious. Consequently, they raided five properties of the Díaz-Parada gang. There they found lavishly-stocked ranches, luxury homes, and a menagerie of wild animals, including a tiger, zebra, antelopes, and monkeys.

Those opulent finds fit the style of Pedro, who was known as El Fresa, the Strawberry, a slang term meaning someone who has high-end tastes. The Strawberry was known for his Gucci clothing, expensive watches, and his buchona girlfriends. Buchonas are women that have large breasts, exaggerated hips, and tiny waists, a body shape achievable solely by surgery so expensive that only cartels can afford it.

The Federales also seized computers with documentation showing Guerreros Unidos payments to Díaz-Parada for helping extort Mixteca businesses and farmers, as well as gifts to the gang, explaining how the Strawberry obtained his properties and animals, and how he financed his high-roller life style in impoverished Mixteca. The Federales concluded that it was in fact the Díaz-Parada gang that conducted the massacre, and had attempted to blame the Tequileros for it.

The massacre killed the municipal mayor and his father, both intimate friends of Pedro Díaz Parada and his brother Eugenio Jesús. Also massacred were eighteen citizens. One of the citizens, Rafael A. G., age thirty, was a foreigner working for the United Nations. Sadly, my instinct about danger to Ralph had been prophetic. We recalled something he had said that night in Little Paris. “No creerse que brindar es cosa sencilla, pero como tengo buena compañía y una buena silla, beberemos y disfrutaremos por un día. ¡Salud!” Not believing that toasting is a simple thing, but since I have good company and a good chair, we will drink and enjoy ourselves for a day. Cheers!

On the night that we learned of Ralph’s death, we lit a candle and placed a caballito of ticunchi beside it. We thanked the spirits that we had indeed enjoyed ourselves that one night with Ralph, a great man who took notice of what needed to be done. Sadly, the wolves had come to his forest.

We sat in our salón with only candlelight to brighten the gloom of reality. What we had all acknowledged, but had not accepted in Little Paris, had been born out – the omnipresent companion of the desire for territory is aggression. That old sage was right. He told that he had reflected on everything that had been accomplished by man on earth, and that he had concluded that everything man had accomplished was futile – like chasing the wind.

Your bag has seen many troubles